In July 1986, in an interview on Canadian radio, Morrissey explained that he thought the Smiths were being excluded by the broadcasting establishment, and that the line ‘hang the DJ’, in the song, ‘Panic’, was about UK radio DJs.

I notice, and I’m sure it’s not an accident, that as the times that we live in become more serious and more critical, popular music, which is such a ferociously fierce and strong art form, goes further and further away from reality. And I almost feel, that it’s almost a political thing. That is, there’s a whitewash occuring, that the nonsensical and useless bland artists are being pushed forward and we’re being force fed. And any groups who dare to confront very real issues, in a very realistic way, are silenced, are gagged. So this is something that we constantly have to fight against. I mean, the Smiths, in England have had 10 consecutive hit singles, and we’ve had huge LPs, and yet, we still are never played on national daytime radio. They will not play the Smiths. I mean, even this week, today, we were the highest new entry in the top 100 with a new single called, Panic, came in at number 18, and they won’t play it. So what can you do? You have to suspect that there’s some, um, fierce political, um, canoodlings occurring… Hang the DJ is a recurring line in the new single, Panic, and once again, as ever, we’re finding problems. I can’t think why, but, um, as I say, this single, Panic, has entered really highly and they won’t play it, because of this line, ‘hang the DJ’. They say it’s offensive. I can’t really imagine why, because when we sing ‘hang the DJ’ live people are ecstatic. This is what they want, to get rid of all these old, boring, middle-aged non-entities, these mediocre people, who are all really controlling the airwaves, and, uh, 50% of the daytime disc jockeys in England are absolutely detested by the people in England. They hate them, and yet here they are controlling our, um, our earlobes, practically. So I’m all for hanging certain DJs. So, watch out. (Morrissey, CHRW London Canada, 29 July 1986)

Less than 2 months later, in September 1986, he was branded a racist for an interview in the Melody Maker, in which the interviewer, Frank Owen, framed his questions using a racist theory that music was divided into warring factions: Indie, which was ‘intelligent’, and made by white people. And Black Pop, which was ‘crude showbiz’, and associated with black people. He also cheerfully opined that ‘Panic’ was about hanging Black DJs. https://illnessasart.com/2020/03/03/melody-maker-27-september-1986/

representing African-Americans as “shuffling and drawling, cracking and dancing, wisecracking and high stepping” buffoons… https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/links/essays/vcu.htm

https://www.radiox.co.uk/artists/the-smiths/smiths-panic-chernobyl-distaster-inspiration-meaning/

It’s not clear if Morrissey understood the theory, or was taking it seriously, and most of the interview was puriently homophobic, and angled to push him into coming out as gay, which he later found distressing.

As written, it’s also not clear, what was asked or what order. It appears to start with, ‘so, is the music of The Smiths and their ilk racist, as Green claims?’ (Green Gartside was the lead singer of Scritti Politti.)

Morrissey replied:

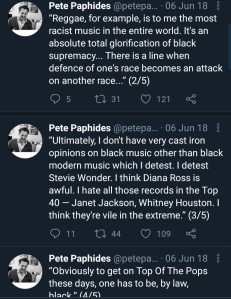

“Reggae, for example, is to me the most racist music in the entire world. It’s an absolute total glorification of black supremacy… There is a line when defence of one’s race becomes an attack on another race and, because of black history and oppression, we realise quite clearly that there has to be a very strong defence. But I think it becomes very extreme sometimes. But, ultimately, I don’t have very cast iron opinions on black music other than black modern music which I detest. I detest Stevie Wonder. I think Diana Ross is awful. I hate all those records in the Top 40 – Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston. I think they’re vile in the extreme. In essence this music doesn’t say anything whatsoever.”

‘Vile’ is hyperbole and Morrissey was airily scathing about nearly everything.

Frank countered that Black music is more subtle because it works on the body via the dancefloor. Morrissey was unconvinced.

“I don’t think there’s any time anymore to be subtle about anything, you have to get straight to the point. Obviously to get on Top Of The Pops these days, one has to be, by law, black. I think something political has occurred among Michael Hurl and his friends and there has been a hefty pushing of all these black artists and all this discofied nonsense into the Top 40. I think, as a result, that very aware younger groups that speak for now are being gagged.”

‘By law’ is a joke. He’d previously used it about himself.

Well, I wouldn’t stand on a table and shout, ‘I’m a feminist’ or put a red stamp across my forehead, but if one tends towards prevalent feminist views, by law, you immediately become one. Likewise, if you have great sympathy with gay culture you are immediately a transsexual. I did one interview where the gay issue was skirted over in three seconds and when the interview emerged in print, there I was emblazoned across the headlines as this great voice of the gay movement, as if I couldn’t possibly talk about anything else. I find that extremely harmful and I simply don’t trust anyone anymore. (Morrissey, The Face, July 1984)

And Top of The Pops producer Michael Hurl, is not black.

It’s Frank who sums it up as a conspiracy by black artists to keep white people out of the charts, ‘You seem to be saying that you believe that there is some sort of black pop conspiracy being organised to keep white indie groups down.’

Morrissey might be trying to fold in Frank’s words, but his suspicion hasn’t changed since the Canadian interview – he still thinks escapist music is promoted by the (straight, white, male) broadcasting establishment:

“Yes, I really do. The charts have been constructed quite clearly as an absolute form of escapism rather than anything anyone can gain any knowledge by. I find that very disheartening because it wasn’t always that way. Isn’t it curious that practically none of these records reflect life as we live it? Isn’t it curious that 93 and a half percent of these records reflect life as it isn’t lived? That foxes me! If you compare the exposure that records by the likes of Janet Jackson and the stream of other anonymous Jacksons get to the level of daily airplay that The Smiths receive – The Smiths have had at least 10 consecutive chart hits and we still can’t get on Radio 1′s A list. Is that not a conspiracy? The last LP ended up at number two and we were still told by radio that nobody wanted to listen to The Smiths in the daytime. Is that not a conspiracy? I do get the scent of a conspiracy. And, anyway, the entire syndrome has one tune and surely that’s enough to condemn the entire thing.”

It wasn’t an outlandish idea:

I remember John Peel saying he believed that if they played the music he played on mainstream radio, people would like it. And I remember thinking, ‘Stupid twat.’ But he was kind of right, if you take a jerky, quirky group like the Arctic Monkeys – that’s what happened. (Johnny Cigarettes, Record Collector, 29 March 2018) https://recordcollectormag.com/articles/bit-chinstroking

“It’s not just us”, says William. “It’s also people like New Order, Echo and the Bunnymen and The Smiths. The Smiths have got a number two LP but you never hear The Smiths on the radio. Steve Wright said ‘people don’t want to listen to The Smiths in the afternoon’. That’s absolutely pathetic! How does he know? “The BBC is supposed to be a public company and we’re all supposed to have a share in it but it’s obviously a dictatorship and those people shouldn’t have that power”. (Jesus and Mary Chain, Smash Hits, July 1986)

Frank asks him if he finds Black music macho (tapping into a racist and a homophobic trope; black men as hyper virile, gay men as effete). Morrissey says it isn’t his world, and adds:

I don’t want to feel in the dock because there are some things I dislike. Having said that, my favourite record of all time is “Third Finger, Left Hand” by Martha and the Vandellas which can lift me from the most doom-laden depression.

Frank accuses him of being a nostalgic luddite (later the NME will accuse him of not wanting black people to prosper in the present, as if 1960s music wasn’t still being played). Morrissey jokes:

‘Hi-tech can’t be liberating. It’ll kill us all. You’ll be strangulated by the cords of your compact disc.’

Frank asks him about violence in Manchester and the lyrics of Never Had No One Ever. Morrissey explains they’re about feeling alienated because he’s Irish:

“It was the frustration that I felt at the age of 20 when I still didn’t feel easy walking around the streets on which I’d been born, where all my family had lived – they’re originally from Ireland but had been here since the Fifties. It was a constant confusion to me why I never really felt ‘This is my patch. This is my home. I know these people. I can do what I like, because this is mine.’ It never was. I could never walk easily.”

Despite this – the interview was the basis for accusations that ‘Bengali In Platforms’, was telling people from South Asia that they don’t belong in the UK. And it gave the NME its excuse for the 1992 homophobic hit piece.

The Frank Owen interview ends with Morrissey reminiscing about his time on the gay scene:

“If the Perry’s didn’t get you, then the beer monsters were waiting around the corner. I still remember studying the football results to see if City or United had lost, in order to judge the level of violence to be expected in the city centre that night. I can remember the worst night of my life with a friend of mine, James Maker, who is the lead singer in Raymonde now. We were heading for Devilles (a gay club). We began at the Thompson’s Arms (a gay pub), we left and walked around the corner where there was a car park, just past Chorlton Street Bus Station. Walking through the car park, I turned around and, suddenly, there was a gang of 30 beer monsters all in their late twenties, all creeping around us… The gay scene in Manchester was always atrocious. Do you remember Bernard’s Bar, now Stuffed Olives? If one wanted peace and to sit without being called a parade of names then that was the only hope… 1975 was the worst year in social history. I blame ‘Young Americans’ entirely. I hated that period – Disco Tex and the Sex-o-lettes, Limmy and Family Cooking. So when punk came along, I breathed a sigh of relief. I met people. I’d never done that before… I never liked The Ranch. I have a very early memory of it and it was very, very heavy. I never liked Dale Street. There was something about that area of Manchester that was too dangerous.”

Frank editorialised with some homophobic language:

‘You big jessy, you big girl’s blouse, Morrissey. But he’s right. It was dangerous and, with the increased media visibility of punk, the violence got worse. You see, punks were not only faggots, they were uppity faggots as well‘.

And an insinuation about cottaging that Morrissey found upsetting:

Because of the public-toilet disparagement, there are of course legal grounds to take action against Melody Maker, but Rough Trade are now making useful inroads with the press because of the Smiths, and they don’t want to cause a fuss, and I am still too green around the gills to ignore their reluctance. I could attempt to tackle Melody Maker myself, but without the label behind me, I am at sea. (Morrissey, Autobiography, 2013)

When it was published, Morrissey was denounced as a racist, then defended, in letters pages and comment pieces. Johnny Marr was angry:

“next time we come across that creep, he’s plastered. We’re not in the habit of issuing personal threats, but that was such a vicious slur-job that we’ll kick the shit out of him. Violence is disgusting but racism’s worse and we don’t deal with it.” (NMW, February 1987)

No one noticed, or was outraged, by Frank Owen’s racist framing or the homophobia.

Tony Fletcher in The Smiths, A Light That Never Goes Out (2012) condemned Morrissey for his ‘no sex’ agenda:

[Frank Owen] dared suggest in writing that in years to come, Morrissey would be into “fisting and water sports”… “Morrissey is the biggest closet gay queen on the planet and he felt that I was trying to ‘out’ him by bringing this up…” If he wanted to play coy, that was his prerogative, although with Thatcherite policies coming down increasingly hard on homosexuality, many other artists had decided to “come out” in response. As Len Brown wrote, “It was a time when everyone – artists and journalists – seemed to be asking the question (politically and sexually) Whose Side Are You On?” To which Morrissey insisted on being individual … a card-carrying member of nothing but his own cult of personality’.

He took out Morrissey’s meandering qualifications to made it sound as if Panic was about a detestation of black modern music so strong that he couldn’t stop himself from harping on:

Not content to leave it there, Morrissey went on to express how much he detested the “black modern music” of Motown descendants Stevie Wonder, Janet Jackson, and Diana Ross, stating, per the lyrics to “Panic,” that “in essence this music doesn’t say anything whatsoever.”

He ascribes Frank’s comments about readers to ‘Morrissey’s thinking’, accepts the racist assumption that Black music is about the body, pretends that British youth didn’t dance before Rave, took ‘by law’ literally and thinks it’s ridiculous to say that escapist music gets more airplay than morose Indie music.

Owen claimed to understand this thinking. “When NME and Melody Maker started putting black acts on the cover,” he recalled, “there was a huge backlash to it. I used to get letters all the time. And it wasn’t explicitly ‘We don’t want blacks on the cover,’ it was more like ‘This is our scene and what do blacks have to do with it?’ ” And so, in his Melody Maker feature, as a response to Morrissey’s own response, Owen tried to answer that question: “What it says can’t necessarily be verbalised easily,” he wrote. “It doesn’t seek to change the world like rock music by speaking grand truths about politics, sex and the human condition. It works at a much more subtle level—at the level of the body and the shared abandon of the dancefloor. It won’t change the world, but it’s been said it may well change the way you walk through the world.” Within a year or two, as acid house exploded (the kindling lit on the Haçienda dance floor) and the rave movement emerged in its wake, a large section of British youth would come to share Owen’s sentiment, the Smiths’ Johnny Marr and New Order’s Bernard Sumner among them. In the summer of 1986, though, Morrissey was still the voice of his generation, which was perhaps why he then dared issue the most ludicrous comment yet of a continually outspoken career: “Obviously to get on Top of the Pops these days, one has to be, by law, black,” which he followed up with an equally ridiculous claim of personal persecution.

He also thought it was suspect that Morrissey liked a sexist song that was released when he was seven years old.

Even the singer’s attempt to restore proceedings mid-interview sounded suspect. “My favourite record of all time is ‘Third Finger, Left Hand’ by Martha and the Vandellas,” he said, citing a (black) Motown single from 1966, “which can lift me from the most doom-laden depression.” And yet this was as stereotypically romantic, conventionally sexist, and thereby nonfeminist a song as had ever been written. It would have said nothing about Morrissey’s life when it came out, and said even less about his life and that of his fans twenty years later. He was in essence employing a double standard, based on what Owen correctly referred to as a “nostalgia … that afflicts the whole indie scene.”

And thought that Morrissey’s comments were a defence of ‘Panic’ rather than in response to Frank’s questions about Indie. While, Frank himself is still blind to the racist assumptions that shaped his division of pop into Black and Indie and thinks Morrissey caused the problem to ‘wind people up’.

As it turned out, Owen wasn’t particularly put out by Morrissey’s comments in defense of “Panic.” “I never thought Morrissey was a racist,” he said. “I always thought it was just a big put-on, that it was just a way to wind people up, the same way that punks wore swastikas.”

28 years later it was the material for a grimly racist and homophobic ‘satire’ by David Stubbs in the Quietus:

…an unspoken racism meant that it was hard for those whose skin was not disco-coloured to get booked on the programme. So, Norrissey hatched a plan. He and the band turned up at the BBC studios one Thursday evening in Afro wigs, their skins applied with burnt cork, minstrel-style. “Hi!” they said, jively, to the man at the door, waving their hands in the sort of way that makes some wonder if Britain is Britain any more. “The name of this here group of ours is The Blackfaces and we’re here to play our new single ‘Strut Your Superficial Stuff’.” Naturally, they were immediately allowed on the show… Then came the moment of revelation, as the “Blackfaces” stopped playing, and rubbed away the dark cork on their faces… this had been the only way a white English group could be smuggled onto Top Of The Pops in the 1980s. They had paved the way so that other white English groups might follow, without wigs or make-up. A black day of the sort they weren’t used to for disco musicians but a breakthrough for England! (David Stubbs, the Quietus, 6 January 2014)

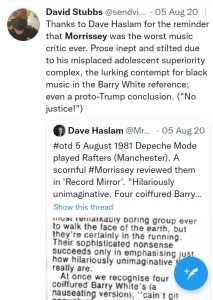

David’s confirmation bias is so strong that he insinuates Morrissey is a racist for comparing Depeche Mode unfavourably to Barry White, and compared him to Donald Trump for using the words ‘no justice’, in a review written to champion his best friend, Linder Sterling’s unsuccessful band, Ludus.

In June 2018 music journalist Pete Paphides, gutted the interview to claim that Morrissey had ‘always’ been repugnant.

And accused Morrissey of ‘trolling’ for using the Attack reggae label in 2004 – nearly 18 years after the Frank Owen interview, and 12 years after Morrissey was accused of racism for holding a Union Jack for less than 3 minutes in front of a crowd who heckled that he was a “poofy bastard“.

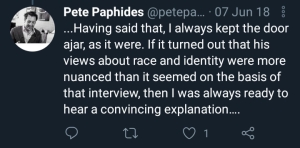

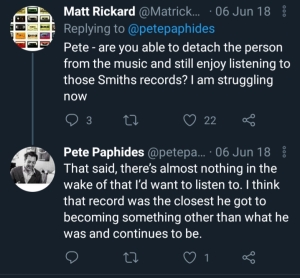

Having failed to see that Morrissey talked about his own experiences of being from an immigrant family, that Frank was mainly trying to get Morrissey to talk about his sexuality and that Morrissey had said that black people had a history of oppression, Pete claims to have always kept the door ajar in case Morrissey’s views about race and identity were more nuanced…

but he can’t listen to most of Morrissey’s work because of what he was and continues to be.

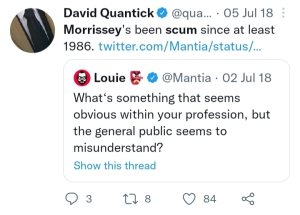

David Quantick thinks that what Morrissey was and continues to be, is scum. And dates it from the Frank Owen interview.

Panic on the streets of London

Panic on the streets of Birmingham

I wonder to myself

Could life ever be sane again?

The Leeds side-streets that you slip down

I wonder to myself Hopes may rise on the Grasmere

But honey pie, you’re not safe here

So you run down to the safety of the town

But there’s panic on the streets of Carlisle

Dublin, Dundee, Humberside

I wonder to myself Burn down the disco

Hang the blessed DJ

Because the music that they constantly play

It says nothing to me about my life

Hang the blessed DJ

Because the music they constantly play On the Leeds side-streets that you slip down

Provincial towns you jog ’round Hang the DJ, hang the DJ, hang the DJ

Hang the DJ….

Side Note: The manufactured and imposed division between Indie and Black music was dubbed the hip-hop wars and played out for most the 1980s and early 1990s.

Frank Owen was interested in hip-hop and house music, but couldn’t get any of the music press in England to cover it, ‘they’d say, “What do you want to write about all these grungy Negroes in there?”‘ https://daily.redbullmusicacademy.com/2013/05/frank-owen-interview

The hip hop wars was just something internal to NME, it really had little relevance to the scene itself… At NME you had a camp of diehard indie supporters on the staff, editors and writers who wanted to put The Go Betweens and The Shop Assistants on the cover. And there was a very vociferous, ideologically determined camp of “soul boys”—also editors and writers–who thought that only black music was valid, relevant, and progressive. They were very scornful of indie music and regarded it as retrogressive, even crypto-racist in so far as it didn’t engage with black culture. But to me the irony was that your indie fans, tending to be college educated, were more likely to have anti-racist, left-wing, progressive beliefs and attitudes than many of the white fans of black pop. It’s just that rap and R&B didn’t speak to them, it didn’t describe their lives. Being middle class, bookish, shy types, they didn’t like the overt sexuality, the materialism, and in rap’s case, the sexism… The indie faction at NME were more in touch with the magazine’s readership, but they didn’t have the strong ideological drive and discipline of the black music faction, so the latter were able to dominate the paper for a while. But eventually they were all ousted, probably I suspect because the owners of NME could see that pushing hip hop through front covers would alienate the readership and lose sales. At Melody Maker we just loved the fact that NME was tearing itself apart. (Mario Lopes, Publico, 11 July 2014) http://reynoldsretro.blogspot.com/2014/11/c86-and-all-that.html

Side Note 2: In 1990, as reported in the Melody Maker, a group of Black American DJs were told how to do ‘dance music’ by Tony Wilson and Keith Allen. Despite the DJs walking out in disgust, neither suffered any career consequences.

Derrick May has had enough: ‘Ma-a-a-n,’ he says, ‘let me tell ya something. Dance music has been fucked up… I have to sit back and see some bullshit Adamski shit… that’s bullshit. On the charts! Number F-ing One! Okay?’ Tony Wilson rises to the challenge: ‘I’m sure The Rolling Stones and The Beatles sounded pretty shitty to the real R&B people but without The Rolling Stones and The Beatles, you’d never have even known you had R&B in America.’ ‘Well I don’t know about that,’ says Derrick… ‘They say it’s not a dictatorship, but it is. We can’t do anything unless you tell us to as much as we try… We – and when I say we, I mean blacks – we all do something and you’ll come behind us and turn it around and add somebody singing to it or some sort of little funky-ass or weak-ass chord line or whatever and get some stupid record company that doesn’t know jack shit about shit to put £50,000 behind it and you got a fucking hit because you stuffed it down motherfuckers throats. So, this group, y’know, has tremendous success and I don’t know what to say, man. I’ve just been busting my ass, it comes from the heart y’know… we as black people have always had to deal with the fact that we’ve had to be better because, since the beginning of time, we’ve had to walk into a white person’s house and clean a white motherfucker’s ass, okay? So don’t tell me.’ This is too much for Keith Allen. He says: ‘Listen Derrick, I might have white skin but I’m black for fuck’s sake! Look at me Derrick – look at me – I’m black.’ Nathan McGough joins in… ‘The whole Ecstasy and House culture from 1988 was like year zero, Pol Pot. The same way as ’76 with the Pistols and anarchy, year zero…’ Derrick May responds… ‘Our DJs are technically better than yours.’ ‘Bullshit. Let’s talk about DJs, right?’ says Wilson… ‘Your Detroit DJs didn’t have one record that was made in the last fucking six months and they wouldn’t play one thing under 130 bpm. They’re all stick-in-the-muds and they should get themselves fucked.’ The insults are starting to fly thick and fast… Egged on by Derrick May, another guy gets up and says white folks think too much about it all while blacks just do it. From where I’m sitting, this sounds a tad close to the ol’ natural riddim argument. But May’s well into it. ‘Yeah,’ he shouts, ‘that’s also the reason why white people can’t play basketball.’ Keith Allen responds in kind; ‘Yeah, but that’s the reason why black Americans don’t ride horses. You’ve got to remember the reason that white guys don’t play basketball is the same reason black guys don’t ride horses.’ Marshall Jefferson gets up and walks out in disgust. (Steve Sutherland, Melody Maker, 4th August 1990) http://dewit.ca/archs/JD/New_York_Story.html